Nostos

There were about a dozen of us for the evening tour at Green-Wood Cemetery. Two young lesbian couples, one third wheel between them, a heterosexual couple who regretted being there as soon as they arrived, three girls who had been day drinking, one Asian tourist who wore a miner’s headlamp, and my friend Lucy and I. We all stood just past the gothic arches of the entrance waiting for our guide when again I caught a whiff of freshly baked bread.

“I don’t smell it,” Lucy said.

The scent had first hit me as I walked up the steep driveway of the cemetery. I had not noticed the large “Baked in Brooklyn” bakery at the foot of the hill, and I was spooked by the smell because it was so out of place. Green-Wood can be a welcoming place in May, with its 475 acres of luscious green grass, dramatic trees, ponds of koi and frogs and geese, flowering bushes of red and violet. It is the home of woodchucks and skunks, a colony of parakeets, even bees, whose honey is marketed as “Sweet hereafer.” Yet there was something unsettling about the scent of bread baking, sweet and warm, at the gateway of a fact as stone-cold as a cemetery.

Green-Wood opened its gates to the dead in 1838, and still accepts new residents every day. Its tombs range from ostentatious to modest. There is a mausoleum shaped like a pyramid, myriads of competing obelisks, monuments topped with Grecian urns, statues of angels, inverted torches, and a spooky structure referred to as “the catacombs,” though it is only the condo version of a mausoleum, and very much above ground.

I was never particularly fond of cemeteries though many who are close to me are. They don’t try to justify their fascination with them, it appears to be self-explanatory. Lucy has been lobbying for a place in the board of one of the historical ones for as long as I can remember. During a drunken night in Palm Springs some years ago she even considered sleeping with one of the other members just so she would increase her chances of getting nominated. She decided against it because he was too old and at risk of dying in the act, which may have damaged her odds rather than help them.

“If killing him meant I would have gotten his spot I would have actually gone through with it,” she later said.

Another friend thinks Green-Wood the best park in New York. She has taken me to several performances there, including one with a dancer diving behind and out of tombstones, which the Times hailed as unmissable and I found awful.

My mother surpasses them all in her enthusiasm about cemeteries. They would be one—if not the first—of her stops at foreign places where she traveled, and she would later speak of them as others did about visiting the Eiffel Tower or the Sphinx. She takes pride in the gems she has discovered among tombstones. Once, in Barbados, she stumbled upon the grave of the last in the line of the House of Palaiologos, the longest running dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, after which our street in Athens is named. She reads the inscriptions on the plaques aloud, as was intended since antiquity when silent reading was not yet a thing. The stone asks us to lend it our voice so that it can speak back to us, tell us their names, their stories, long after people are gone.

“Imagine,” my mother will say tomb-side, “The lives they had.”

From the Epigraphic Database, N. Black Sea ca. 50 BC-50 AD

Source: Sententiae AntiquaeTheiophilê Hekataiou gives her greeting.

They were wooing me, Theiophilê, the short-lived daughter of

Hekataios, those young men [seeking] a maiden for marriage.

But Hades seized me first, since he was longing for me

When he saw a Persephone better than Persephone.And when the message is carved on the stone

He weeps for the girl, Theiophilê the Sinopian,

Whose father, Hekataios, gave the torch-holding bride-to-be

To Hades and not a marriage.Maiden Theiophilê, no marriage awaits you, but a land

With no return; not as the bride of Menophilos,

But as a partner in Persephone’s bed. Your father Hekataios

Now has only the name of the pitiable lost girl.And as he looks on your shape in stone he sees

The unfulfilled hopes Fate wrongly buried in the ground.Theiophilê, a girl allotted beauty envied by mortals,

A tenth Muse, a Grace for marriage’s age,

A perfect example of prudence.

Hades did not throw his dark hands around you.No, Pluto lit the flames for the wedding torches

With his lamp, welcoming a most desired mate.Parents, stop your laments now, stop your grieving,

Theiophilê has found an immortal bed.

We did not need a guide to pilgrimage to the resting places of the famous, we could use a map for that. In death, the famous become less interesting because we already know too much about their lives. Their glory and terror has been diminished by death, and their legacies are at the mercy of our interpretations. They’ve no control over the symbolism assigned to them by fans: Oscar Wilde’s memorial in Paris was soiled by a thousand lipstick kisses, and white supremacists have been leaving tiny American flags on Bill the Butcher’s gravesite in Brooklyn.

It was the strange stories of the dead who led ordinary existences like our own that most fascinated us. After it is gone, a common life is elevated to the mystical. Every tombstone and mausoleum held a secret for us to unlock. Our guide told us of Mary Rogers, “The Beautiful Cigar Girl,” whose violent murder inspired a poorly imagined story by Edgar Allan Poe, of a heroic drummer boy who at the age of eleven volunteered to serve in the Civil War, of an eccentric rich lady who held a highly publicized and illegal burial there of her beloved pet dog, of brothers who fought on opposite sides and died from wounds incurred in the same battle, of artists who tried to make it in life but became a much better story in death. We stepped on their graves, tourists and strangers, some of us drunk and others bored, too young to die, or long past the age they reached, all of us still so full of bread, warm and sweet and effervescent, then moved on to the next one because time was flying.

The question I’ve wondered most about while standing by a gravesite is whether the person in it would have wanted to be buried there or not. In my family, we’ve always talked about where we desired to be buried, and the topic has even resulted in disputes. My grandfather was adamant about being buried in his village. He had invested in his gravesite years before his actual death, built the whole thing so that only the date would need to be added, and visited it often to admire and dust it, as though he was paying a visit to his future dead self. His village was several hours north of Athens, mountainous and inaccessible, and my grandmother, who was more social, feared that if she were to be buried there with him, nobody would ever visit her to tell her “the news.” She had given orders to be buried somewhere near our house, but after my grandfather passed away she changed her mind. When her time came, nine years later, she went in the same hole, on top of him. Now my mother and her sister also want to be buried there—the farthest possible, they joke, from their own husbands. This will be easily accomplished, as my father wants to be buried in his own family grave on the island of Cephalonia. I had no choice but to think of the question myself and decided that of the two I would rather also go in that same grave of my mother’s side, just because I like the idea of us being packed in it like sardines. Besides, it is a beautiful village, quiet and quaint, with a green, heavenly view.

I’ve now been gone from Greece for over half my life but there is comfort in keeping that destination in mind. As Svetlana Boym put it, “At first glance, nostalgia is a longing for a place, but actually it is a yearning for a different time—the time of our childhood, the slower rhythms of our dreams.” Roots, I think, have more to do with what we long to return to than where it is that we came from.

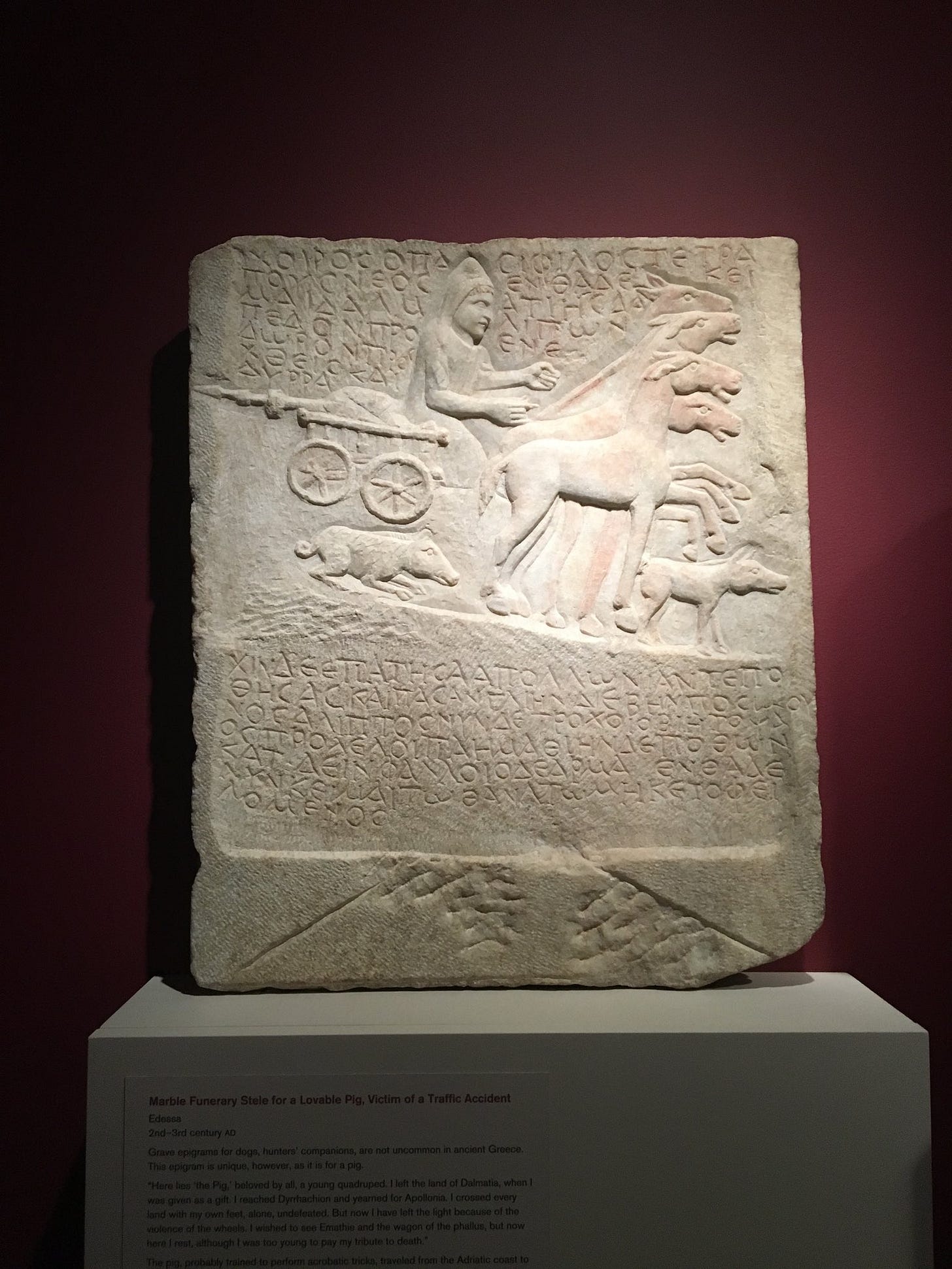

One of my favorite tombstones is that of a pig. He died under the wheel of a chariot in a traffic accident on Via Egnatia, sometime in the second or third century. The inscription, which is written in dactylic hexameter, reads:

A pig, friend to everybody

a four-footed youngster

here I lie, having left

behind the land of Dalmatia,

offered as a gift,

and Dyrrachion I trod

and Apollonia, yearning

and all the earth I crossed

on foot alone unscathed.

But by the force of a wheel

I have now lost the light,

longing to see Emathia

and the chariot of Phallos

Here now I lie, owing

nothing to death anymore

The pig’s story is lovable and funny, but has tragedy in it: he died on the hero’s journey, leaving his home in Dalmatia, and getting killed on the road to Emathia, which, the stone tells us, he was longing to see. He is now forever bound by death to Edessa, where the accident took place and his journey was cut short.

I mourn most those who were buried in strange places that held no meaning for them, those who did not get to return to whatever it was they longed to return to, but died and were buried in Edessa, owing nothing to death, and with death owing them a piece of bread and a ticket home.

Ahhhhhh, Sophia, you caused a good ache in my chest.

The valiant pig will live on in my heart with Robbie Burns' "mouse."

Every couple of weeks or so, my mom has a call with a cousin back in Poland. He lives in Krakow but an important topic of conversation on each call is the state of various tombstones in a village cemetery 2 hours drive north of the city. My grandparents and several other family members are buried there, and whether the tombstones are in good shape is information that travels regularly across the Atlantic. Cemetery culture is fascinating. My current wish is just to be dealt with in whatever way least impacts the environment; I wonder whether that will change over time.